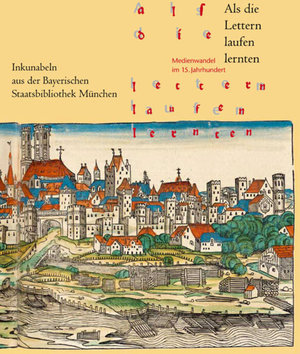

»Als die Lettern laufen lernten«

Medienwandel im 15. Jahrhundert. Inkunabeln aus der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek München

Die Erfindung des Buchdrucks durch Johannes Gutenberg wird häufig als «Medienrevolution» bezeichnet und mit den Auswirkungen der «elektronischen Revolution» der vergangenen Jahrzehnte verglichen, denn beide Geschehen führten zu tiefgreifenden Veränderungen der Herstellung und der Verbreitung von Texten. Die Ausstellung möchte demgegenüber veranschaulichen, dass in der zweiten Hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts nicht ein plötzlicher Umbruch, sondern ein allmählicher Ablösungsprozess stattfand. Zwar wurden bei der Buchherstellung zunehmend Drucktechniken eingesetzt, aber die ältesten Drucke, die Wiegendrucke oder Inkunabeln, weisen immer noch zahlreiche individuelle Charakteristika auf, die von Hand erzeugt wurden. Innovation und Tradition überlagern sich so in vielfältiger Weise: die modernen Techniken zur gedruckten Vervielfältigung von Texten und Bildern, etwa der Holzschnitt und der Druck mit beweglichen Lettern, verdrängten das Abschreiben von Hand nur langsam, und gedruckte Bücher wurden noch über lange Zeit von Hand korrigiert, mit farbigen Überschriften und gemalten Bildern ausgestattet.

Aus den reichen Inkunabelbeständen der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, die mit über 20.000 Exemplaren weltweit eine Spitzenposition einnimmt, werden etwa 100 Stücke gezeigt. Im Mittelpunkt stehen die «Gutenberg-Bibel» und der «Türkenkalender» von 1454, ein Unikat der Münchener Sammlung. Neben Bildhandschriften und Blockbüchern sind Wiegendrucke mit gemalten Miniaturen und herausragende Beispiele der Holzschnittillustration zu sehen, etwa der Bericht des Mainzer Domherrn Berhard von Breydenbach über seine Reise nach Palästina, Hartmann Schedels persönliches Exemplar seiner «Weltchronik» und Sebastian Brants «Narrenschiff», für das Albrecht Dürer zahlreiche Bilder entwarf. Gezeigt werden auch Beispiele für andere druckgraphische Verfahren, wie der Kupferstich und Metallschnitt sowie der Farb- bzw. Golddruck. Einblicke in die Abläufe bei der Herstellung gedruckter Bücher geben Probedrucke und gedruckte Rubrikatorenanweisungen. Wie leistungsfähig Druckereien schon im 15. Jahrhundert waren, belegen Wiegendrucke in nichtlateinischen Schriften und in ungewöhnlichen Formaten ebenso wie Zeugnisse für Auflagenhöhen gedruckter Bücher und den Buchvertrieb. Mit dem Eintrag eines Käufers von 1494, der sein Erstaunen über den geringen Preis einer Inkunabel zum Ausdruck bringt, endet die Ausstellung. Vierzig Jahre nach der «Gutenberg-Bibel» hatte sich der Buchdruck am Markt endgültig gegen die Konkurrenz älterer Verfahren der Textverbreitung durchgesetzt.

The invention of printing with movable letters by Johann Gutenberg is frequently described as a „media revolution“ and compared to the effects of the „electronic revolution“ of the past decades. While both events had far-reaching consequences on the production and distribution of texts, the exhibition intends to demonstrate that a gradual transition rather than a sudden turnover took place in the second half of the 15th century. Increasingly, printing techniques were employed for the production of books, but the oldest printed books, traditionally referred to as incunabula, still show many individual features which were created by hand. Thus, innovation and tradition overlap in many respects: the modern techniques for multiplication of texts and images in print only gradually superseded handwriting, and for a long time, printed books continued to be corrected by hand and to be decorated with coloured headlines and painted illustrations.

About 90 items are displayed from the rich holdings of incunabula in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, which ranks first among all libraries world-wide with holdings of more than 20,000 15th-century books. The most famous incunabula are on show in the „Schatzkammer“ (treasury), including the Gutenberg-Bible and the „Türkenkalender“ of 1454, the earliest printed book in German, which survives in a single copy held at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. In addition to illustrated manuscripts and blockbooks, incunabula with painted miniatures and outstanding examples of 15th-century woodcuts can be seen, among them the report by the Mainz canon Bernhard von Breydenbach about his journey to Palestine, Hartmann Schedel’s personal copy of his „Nuremberg Chronicle“ and Sebastian Brant’s „Ship of Fools“, for which Albrecht Dürer may have designed illustrations. Apart from woodcuts, examples of other techniques for printing illustrations are presented, like copper engravings, metal cuts and printing with colour and gold - still at an experimental stage in the 15th century.

In the second part of the exhibition, a range of very diverse incunabula give insight into the production and distribution of printed books - starting with the manuscript copy text used for typesetting and ending with the book arriving in the hands of a buyer and reader. Proof-sheets and printed tables of rubrics reveal how early printers organized the production of books. In the first decades of printing, modern conventions of book design like title-pages developed. Texts printed in non-Latin alphabets and unusual formats as well as evidence for 15th-century print-runs demonstrate the effectiveness and capability of early printing workshops. The new medium of the broadside reached entirely new groups of readers. In the printing press, posters and handbills could be produced in large numbers and thus served to disseminate all manners of texts - from pious songs over medical advice up to current news. Early printers also used broadsides to advertise their products in order to achieve financial success. This, however, led to a rapid decrease in book prices: The exhibition ends with a note added to an incunable in 1494 by a buyer who marvels at the low cost of the book. Forty years after Gutenberg published his Bible, the technology of printing finally prevailed over older, competing forms of text reproduction. While conservative circles continued to plead for copying texts by hand, the printed book’s triumph proved unstoppable, even though some readers, like Sebastian Brant’s „foolish reader“ could not cope with the massive number of books available.